.

Think you know about Richard III? Think again! In this interview with historian Matthew Lewis, we gain some fascinating insights into this intriguing medieval king. Read on, keep an open mind, and enjoy!

.

.

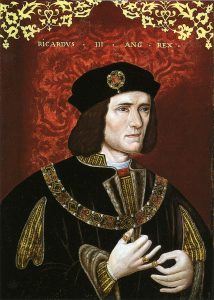

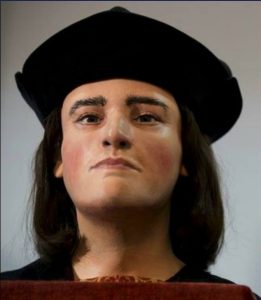

What three words would you use to describe Richard III’s character?

I would say loyal, progressive, and naïve. Loyal is a word he used to describe himself in his motto Loyalty Binds Me. It probably seems like a contradiction if you believe in the traditional history of his betraying his brother and his nephews, but I don’t, so it works for me and can be seen running through various aspects of his life.

Progressive refers to Richard’s legal views and activities. He had a long and strong track record of defending those lower down the social ladder against their superiors. It wasn’t the way society worked in 15th-century England, and I think it upset and unnerved a lot of powerful people, particularly when Richard became king. We can see those interests and concerns carried through to his parliament in 1484. It’s a good example of an unbroken thread from his youth that suggests there was no monstrous change in personality in 1483.

Naïve is a word I use for both Richard and his dad. I think they both failed to see the schemes and ulterior motives of those around them. They blindly accepted the word of people who would turn out to be duplicitous. If you want to succeed in 15th-century politics, one thing you can’t be is naïve.

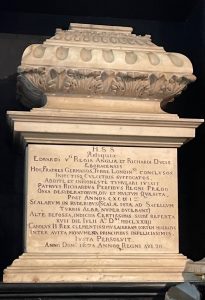

Window in York Minster depicting Richard III’s coat of arms and motto:

Loyaulte me lie – Loyalty Binds Me

What sparked your own interest in Richard and the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower?

I did history at A-level and we studied the Wars of the Roses. Thanks in no small part to a fantastic teacher, I was gripped completely by the whole period. It hasn’t released that vice-like hold on me ever since. Richard III and the Princes in the Tower is almost like the climax of the period. It’s where most studies of the Wars of the Roses end, so often it’s the final dramatic scene before the curtain comes down. For me, the scarcity of sources, the contradictions within them, and the human behaviour of those involved in 1483-5 made it an endlessly fascinating topic. Few people in history are pure good or pure evil, and the idea that Richard III might not be this monster crafted from much later sources demanded exploration.

The Murder of Rutland by Lord Clifford – the drama of the Wars of the Roses as depicted in this

19th-century painting by Charles R Leslie. Edmund, Earl of Rutland, was Richard III’s elder brother. He was only 17 when he died at the Battle of Wakefield.

Why do you think there are so many passionate Ricardians, all over the world? What is it about this man that inspires such loyalty?

I think it’s often born of a sense that the Richard III presented to us by traditional accounts of his history doesn’t seem to resemble the Richard we can see in the contemporary sources. It’s easy to see a man who has been treated incredibly badly by history, presented, a Ricardian view would suggest, as something he wasn’t, to serve the political ends of others. If we see that man, and we see he has no way to defend himself, I think it’s human nature to want to step in and provide that defence. In life, I think Richard was anything but defenceless, but in death, his family and dynasty gone, he, and his reputation, are left languishing in a dungeon.

Melodrama all the way – the pantomime villain version of Richard III,

as portrayed by Laurence Olivier in the 1950s

Beyond that, his is a complex history that requires deep investigation and thought to understand. The academic exercise of working out who he was and what he did, and didn’t do, is a challenge that defies completion. That’s a temptation to many.

Ultimately, I think there is no one reason why people become interested in Richard III. It will appeal or grab attention for a variety of reasons. If some aspect of Richard’s story speaks to someone on a personal level, reflecting some aspect of their own life, or drawing on a distaste for perceived injustice, these can be powerful motivators. The widespread interest demonstrates that these things appeal to something in human nature, something we all share and that brings us together.

Those bones in Westminster Abbey that are said to be the Princes’ remains – do you think DNA would answer the question once and for all? Or is it likely to be too contaminated? Do you think the Crown will ever allow the bones to be tested?

I don’t think the remains would prove to be those of the Princes. If there is viable DNA in the urn, we would be able to answer the question of their identity once and for all. We have their uncle’s DNA and their mother’s mtDNA too. Even something non-destructive like radiocarbon dating might answer the question straight away. If these remains are, for example, Iron Age, or Anglo-Saxon, then they aren’t the Princes.

At present, the Crown won’t allow an examination of the remains. Westminster Abbey is a royal peculiar, meaning that the monarch effectively owns it and controls it. That may change one day, but for now, we aren’t going to be allowed to test them. One of the problems with the urn is that it might answer some of our questions, but it can’t answer all of them. If they are the remains of the Princes, they can’t tell us who killed them, nor probably how. It would mean they didn’t survive beyond a certain date, so narrows down the debate, but still leaves a mystery. It they aren’t the remains of the Princes, that doesn’t mean they weren’t murdered in 1483 by Richard III, just that they weren’t buried there (let’s face it [the Tower of London] is a crazy place to bury them anyway). It would mean they might have survived, but still might not have, leaving the mystery still unsolved.

.

.

Richard had some interesting ideas for improving the lot of the common man. Can you give us a couple of examples?

He really, genuinely did. Before I offer some examples, I think it’s important to consider what this fascination of Richard’s meant. I don’t mean what it said about him (it suggests he was a nice, compassionate man with a social conscience) but rather what it meant for him politically. The first point to consider is what Richard gained from an attitude of helping those at the bottom of the social ladder against their superiors. He gained nothing. It was an age of bastard feudalism in which men got rich and powerful by building their private army. That came with turning a blind eye to thuggery and defending those in your service who broke the law, often lifting them out of legal proceedings. By failing to adhere to this broken, corrupt system, Richard shunned that kind of easy power. What does that say about him?

Secondly, what did others make of Richard’s behaviour? His policies often hurt those with power in order to benefit those he saw being wronged. That’s one thing in the King’s [Edward IV’s] little brother, off in the north where no one really cared (or was much affected by) what he did. When he became king and continued to pursue this interest, he became a serious threat to those who thrived on the system’s faults and the corruption that it spawned. I would suggest that most of those who left England and sought out Henry Tudor did so because they were unhappy with Richard’s socially progressive policies that were taking money out of their pockets to improve the lot of others. If those were his enemies and their motivations, I know whose side I’d be on.

In terms of examples, as Duke of Gloucester he ordered the removal of fishgarths from rivers. I know, obscure, but important. Fishgarths were industrial fish catching operations that blocked rivers. This made waterways impossible to navigate and reduced the catch down river. Richard ordered all fishgarths in the north-east to be removed, and he began by having any on land he owned taken out. No hypocrisy here. There was years of resistance to this. Those who erected fishgarths were necessarily the wealthy landowners. Those who benefitted from their removal were ordinary people. Most noblemen would be careful not to upset powerful, vested interests just to help those whose support offered no practical benefits. Richard did it.

The remains of a medieval fishgarth. This one is in Anglesey.

There are lots of other examples, too. Katherine Williamson brought the murder of her husband to Richard’s attention. The three brothers accused of the murder, helped by their father, had got into Richard’s service, hoping his protection would help them avoid any consequences. The corrupted system of livery and maintenance in operation by this point meant that those in a lord’s service would expect him to shield them, no matter what they’d done. When Richard found out, he had the father arrested and sent to jail to await prosecution. The brothers fled, but Richard ensured efforts were made to find them and bring them to justice. This meant Richard was deliberately shunning the opportunity to bolster his numbers with thugs and criminals to make his faction more powerful. What does that tell us about him as a person?

The interesting thing is that we can clearly see this interest continuing when Richard becomes king. His parliament in 1484 introduced a number of measures to improve access to justice for the common people. Bail was being frequently denied, and a person’s goods were being seized when they were arrested with no requirement to give them back if acquitted. That might mean a false or malicious accusation could cost a person everything they owned, the tools of their trade, the way they fed their family. Parliament reformed bail laws, empowering justices to seek out, correct, and punish instances where bail had been unfairly denied. The law was also changed so that goods couldn’t be seized until a person had been convicted in court. A manifestation of the notion of being innocent until proven guilty. Corrupt jury practices were reformed, land fraud outlawed, weights and measures enforced, trade laws reformed.

There are two main reasons I think this is an important aspect of Richard’s story. Firstly, it helps to understand why some abandoned him in 1483-5. They wanted the corruption that made them rich back. Secondly, many will say that Richard’s policies as king were desperate bids for popularity to keep his crown. I’d suggest they were anything but. In fact, they were probably the opposite. We can demonstrate an unbroken thread of interest in equity and justice throughout his adult life, and I think his naïve and clumsy attempt to press his policies onto the national stage contributed more than anything else to his downfall. He shunned corrupt thugs, and they made for powerful enemies.

If Richard hadn’t lost at Bosworth Field, what do you think he would have said or done regarding the mysterious disappearance of the Princes?

It’s impossible to be sure, and depends on whether they were alive or dead, and if they were dead, what part he had in their demise. All of those remain unanswered questions at the moment. I tend to think he didn’t murder them, that they were never in any danger from him, and that both survived his reign under his protection. Not a popular view in many quarters, I know, but the point is I can’t prove that. If Richard had killed them, I think he had the perfect opportunity at the October 1483 rebellions led by the Duke of Buckingham to blame those conspirators and put the matter to rest forever. That he didn’t do so is, I think, interesting. If Richard had reigned longer I think we would have found out with more certainty what happened to his nephews one way or another. If they weren’t killed but instead protected by Richard, as I believe, then they may have stepped onto the political field as adults, the idea (hope?) being that they would be loyal to Richard’s government.

It might sound like a stretch, but that’s exactly what had happened with the Mortimer bothers in 1399. They were considered by most to be the heirs to Richard II when Henry IV usurped the throne. They were taken into lose custody, abducted, recovered, placed into tighter custody and on Henry V’s accession, released as adults. The younger died not long after, but Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March went on to serve the Lancastrian regime faultlessly until his death. He even exposed the Southampton Plot, which aimed to put him on the throne. The part of this template that failed was the early lose custody that led to abduction and use against the king. If I was Richard, I’d cut that bit out and go straight to the part where no one knows where they are, raise them to hopefully be loyal, and deal with them as adults if they proved not to be. Sounds like an equitable approach for a man steeped in equity, even when it was a risk to him. That would mean that around 1493, when Edward V was 21, we might have seen him, and his brother, emerge onto the political stage. What they might have done next is, I guess, another story.

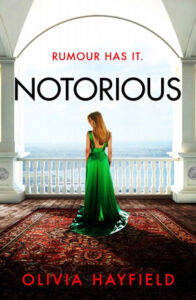

Enormous thanks to Matt for his thoughtful answers to my questions. If you want to know more (of course you do!) I highly recommend his books, documentaries and podcasts. Popular history at its best! Thanks also to Matt for his assistance with the historical note in Notorious, my modern retelling of the mystery of the Princes in the Tower.

About Matthew Lewis:

Matthew has been popping up on TV and the internet a lot recently. You may have seen him arguing (persuasively!) the case for Richard III during Lucy Worsley’s BBC2 documentary about the Princes in the Tower. His documentaries and podcasts are a must-watch for anyone interested in history, particularly the medieval period and the Wars of the Roses. Find out more at: https://www.mattlewisauthor.com/